|

Listen to Post

|

Listen to this article now:

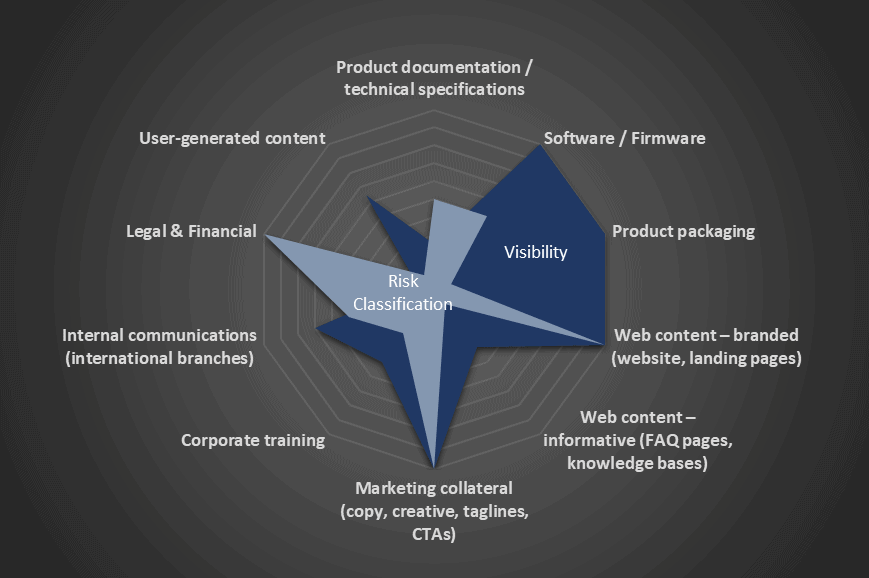

A mapping of different quality levels to content types according to their visibility and risk classification

Translation quality has long triggered fervent discussions on the topic. Debaters range from scholars and the academia to professional translators and reviewers alike, language service companies and translation buyers. The questions also span from what quality is in translation to how it can be measured objectively and by whom.

Different quality assessment models have emerged over time to serve the localization industry and create a common ground for discussion among its stakeholders. One first widely accepted such standard was the LISA QA Metric inspired by the Localization Industry Standards Association. The LISA model emerged mainly as a quality assessment method targeted specifically at the software and hardware industries, at a time when translation was heavily dependent on the technological boom. However, since then the need for translation and localization has spread throughout the whole spectrum of content types, and the LISA model slowly but steadily became outdated as it focused primarily on error categories of linguistic nature, such as translation accuracy, grammar and syntax, and failed to account for content types where style and cultural appropriateness were a priority.

Nevertheless, the more translation penetrated new industries and content types, the bigger was the need for a more comprehensive and inclusive quality assessment model that would be flexible enough to tackle the intricacies surrounding the numerous content types, as well as to satisfy all parties involved and hence minimize the moderation and rebut processes.

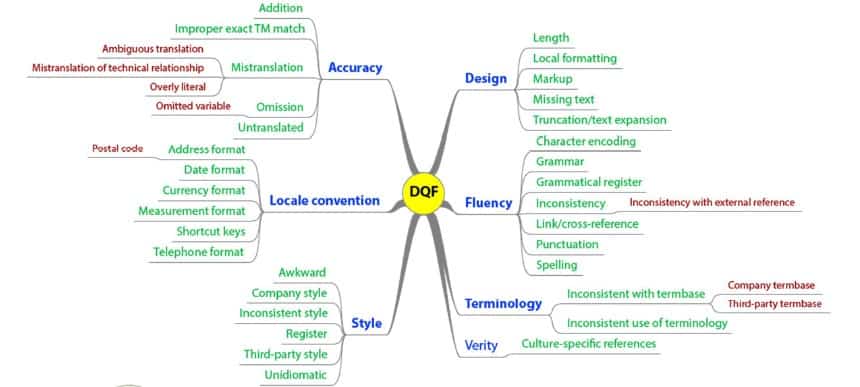

According to TAUS and their Dynamic Quality Framework (DQF), error typologies in translation and localization can pertain to accuracy, locale convention, style, design, fluency, terminology and verity, with a subset of error categories in each.

The flexibility of this error typology lies in the fact that the purpose of the content determines the relevance and the severity of the error and to explain this better, here are some examples:

Accuracy is an extremely important factor when translating the instructions for use of medical or surgical equipment, but although a mistranslation can be classified as a critical error in terms of severity -there are mistranslations that can lead to product recall as they can potentially result in loss of life- the addition of an explanatory text may not be characterized as an error at all if it enhances readability.

On another note, locale conventions such as currencies and address formats are extremely relevant when localizing e-commerce sites, as they may curb conversions or even logistically-speaking hinder product shipping leading to low consumer engagement and customer satisfaction. Still, they will not probably be classified as critical errors when localizing the registration page on a blog site.

Pic 3 – Importance of locale conventions accuracy in e-commerce site content and blog site

Style and terminology are two, one would say, mutually exclusive categories; where style is a priority, translation gives its place to transcreation or even copy authoring in the target language, at least in some contexts. This is usually the case with marketing and promotional content. While company terminology may be available and used as a quality assurance factor for other content types, such as product manuals, it would not really make sense to check a copy that has been re-written, not really translated, against approved terminology. Instead a style guide may prove handier in this case.

Besides the intent of the content, the selection and relevance of quality factors is also highly affected by the visibility of the copy and its risk classification – the latter defined according to the estimated cost or likely impact, likelihood of occurrence, and countermeasures required in case of failure. Therefore, mapping your different content types on the above quality factors, and adding different severity levels and weights, your professional translation partner can create very specific content quality scoring profiles to evaluate their localized counterparts. This is no small feat, but once you get over this, you will be able to gather valuable translation-quality-related data to improve quality scoring on existing localized content, as well as to adjust and apply on new content types.

Once you have defined the quality profiles for the different types of your content, you can also consult them for budget allocation when considering adding new content to your localization strategy. Besides serving as a quality index for assessing and improving the efficiency of your localized content – whatever the intended purpose is every time – quality profiles can also be used for selecting the appropriate service levels when it comes to translating content. So, for user-generated product/service reviews for example, which would be categorized as medium-visibility and low-risk content, you could do without professional human translation, but instead select the raw output of machine translation which would by the way be the most economical localization option. While on the other hand, if you were thinking of adding the translation of your quarterly financial results to your budget, then you would probably need to budget for a more comprehensive translation workflow, which would ideally include translation, editing and proofreading, and require a bigger spend.

Whatever is the case, we are always glad to help. Don’t hesitate to contact us.